It’s a problem when journalists at prominent publications warn consumers not to purchase items they see advertised online because the products are likely to be overpriced and kind of suck.

And it’s a problem when researchers at a prestigious research university offer empirical evidence that behavioral advertising doesn’t have the consumer’s welfare at heart.

And it’s a very, very big problem with government officials in the US and Europe warning that people can use programmatic advertising for racist purposes, which can lead to the undermining of democracy.

And yet these things happened.

First, Julia Angwin of the New York Times wrote an article warning consumers not to purchase stuff they see advertised online. Why? Because, she writes, the ads that are highly targeted — i.e., ads that are delivered programmatically — hawk products that are more expensive than they need to be and inferior products that can easily be purchased elsewhere.

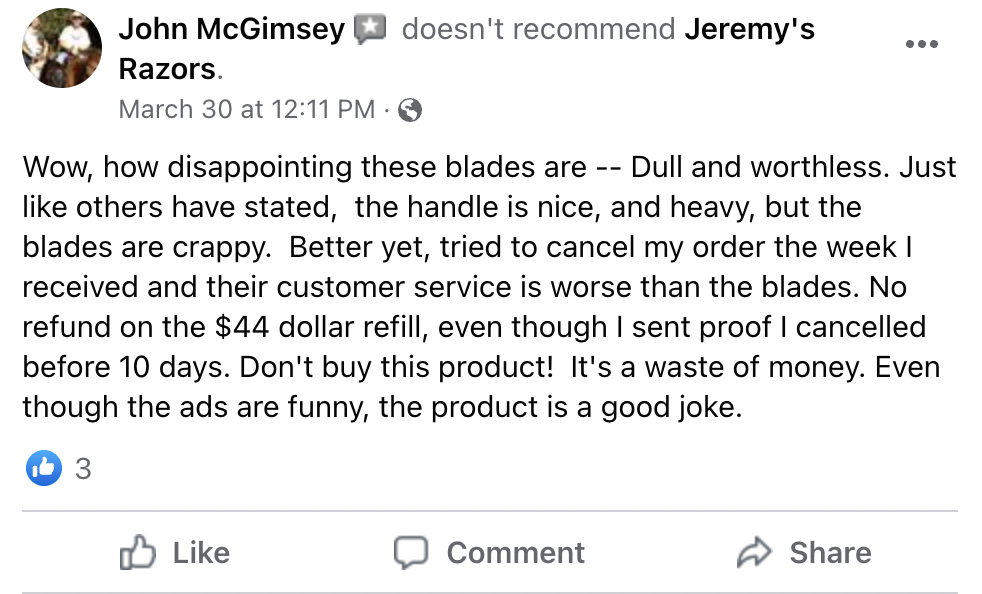

She offers up Jeremy’s Razors as a case in point. Its cringe-worthy “woke free” tagline targets hypermasculine men and contributes to the toxic discourse in the country. But divisiveness is all the brand really has to offer. An abundance of bad reviews warns would-be buyers to stay away from the brand.

Microtargeting based on behavioral data was supposed to be a good thing for all parties involved in the equation: brands, publishers and consumers. But those benefits haven’t panned out.

It hasn’t been suitable for publishers. As advertisers pivoted away from traditional advertising to microtargeted programmatic campaigns, revenue for global newsletters fell from $107 billion in 2000 to nearly $32 billion in 2022, according to GroupM.

And it’s not good for advertisers, as all brands lose when poor quality ads proliferate, leading journalists to warn consumers. And, all advertisers lose when sleazy brands leverage microtargeting to a dog whistle.

Writes Angwin, “Microtargeting has also enabled advertisers to discriminate in ways that are hard for regulators to catch. It is illegal, for example, for advertisers to use language in their ads suggesting that jobs, housing, or credit opportunities are being offered to people of a certain race, gender, or age or in other protected categories. But ad targeting means that advertisers can hide their preferences in the algorithm. Facebook has repeatedly been shown to have enabled discriminatory advertising.”

This isn’t a new phenomenon. In 2016, the Senate Subcommittee on Intelligence found that Russian operatives targeted African Americans with Facebook ads discouraging them from voting.

And microtargeting is bad for the consumer because it creates conditions that allow brands like Jeremy’s Razors to rip them off. A report from Carnegie Mellon University researchers, Behavioral Advertising and Consumer Welfare: An Empirical Investigation, showed that products offered via targeted advertising are 10% more costly and sold by lower quality brands, as measured by BBB ratings.

According to a European Commission report, this level of messaging and microtargeting is bad for society and proves it’s time to reform the digital advertising ecosystem.

Saving Programmatic

I’ve written before about the industry’s need to pay attention to the bad ads that flood the ecosystem and cause a world of harm to consumers. Granted, the ads I wrote about in that article were outright malvertising, and the ads the New York Times, Carnegie Mellon Researchers, and the EU regulators are warning against are legitimate in that they can lead to transactions in which the consumer receives a product, albeit a crappy one.

Still, the industry needs to better screen for these types of ads that slip through the microtargeting filter. It’s not hard to guess the sentiment behind a brand that promises it is “anti-woke.”

It’s also not hard to prevent such ads from appearing on a platform or publication if the publisher has the right tools. Tools available on the market can assess the content and images on an ad and its landing page for dog-whistle messaging. These tools give publishers a lot of control over the types of ads that appear on their sites. Of course, there’s a cost involved, but it may be well worth the effort if it means saving digital advertising. Advertising, after all, still largely funds the Internet.